Memphis. 1959. A city in flux. A city at the nexus of a cultural revolution. Racial segregation has a stranglehold on the deep South and tensions run high. Yet, change permeates the air in the form of music being released from Sun Studios and broadcast over the radio.

Rock and Roll. Rhythm and Blues. Music that becomes universal for all races. That's the story we know about.

But there is something else happening in Memphis during this time; an unlikely element that became, on one hand influential in racial desegregation, but also united a city and changed an institution forever.

Wrestling had already been a part of the Memphis landscape prior to 1959, but it was the combination of business prowess between Nick Gulas and Roy Welch that was changing that landscape since they came into the territory in 1957. Gulas, often characterized as miserly (to put it nicely) when it came to wrestler payouts, was the outspoken mastermind of the Tennessee wrestling machine, while Welch was the quite force behind the scenes and in the locker room. (Welch's son, Buddy Fuller, would work as the local promoter in the area starting in November 1958, showcasing the events at Ellis Auditorium in Memphis.)

Memphis was just one city in the small empire that Gulas and Welch had taken over in the South that stretched east to Nashville and south into Alabama. Media coverage to drum up ticket sales and attention toward the product was traditionally and consistently relegated to newspaper or radio coverage. That was the standard form of advertisement. But Gulas, the savvy and forward-thinking businessman he was, pushed television broadcasts as a method to draw fans to the live shows.

Gulas' tactic was simple: start a feud on the television broadcast (most of the time on Saturday nights) and hype the grudge match for the following live show. Not too dissimilar to how wrestling is booked today, but it worked. In Memphis, Fuller's broadcasts would be shown on WMC Channel 5 (soon after WHBQ Channel 13), hosted by Memphis sports announcer Jack Eaton.

…

Prior to 1959, Memphis was already booming with plenty of wrestling talent in the form of Gorgeous George, Dick Hutton, and others who came to town, but it was the arrival of two men in particular who became focal points in taking Memphis wrestling to another level of popularity and providing in-ring counterparts to the Gulas/Welch/Fuller marketing and booking genius.

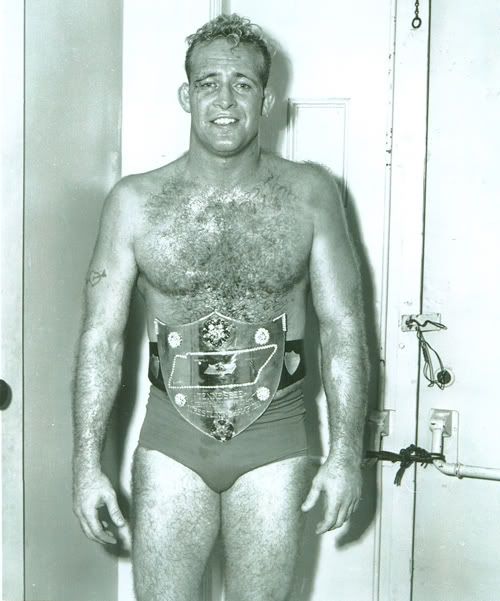

Late in 1958, Billy Wicks, who had worked in other southern NWA territories in Alabama and Florida, arrived on the Memphis scene with his Gulf Coast Championship title. He might have dropped the belt to Spider Galento soon after his arrival, but Wicks would quickly recover and be put into a program with the aforementioned George, who was undoubtedly the most well known wrestler as the time. This was also Fuller's first crack at the local booking roll he inherited after buying the rights from Les Wolfe.

Wicks had an immediate appeal with Memphis fans as a small but tough blue collar appealing character. The perfect foil to the glamor boy image of Gorgeous George. They're contest in December of 1958 ended in a tie, one fall a piece in a best of three.

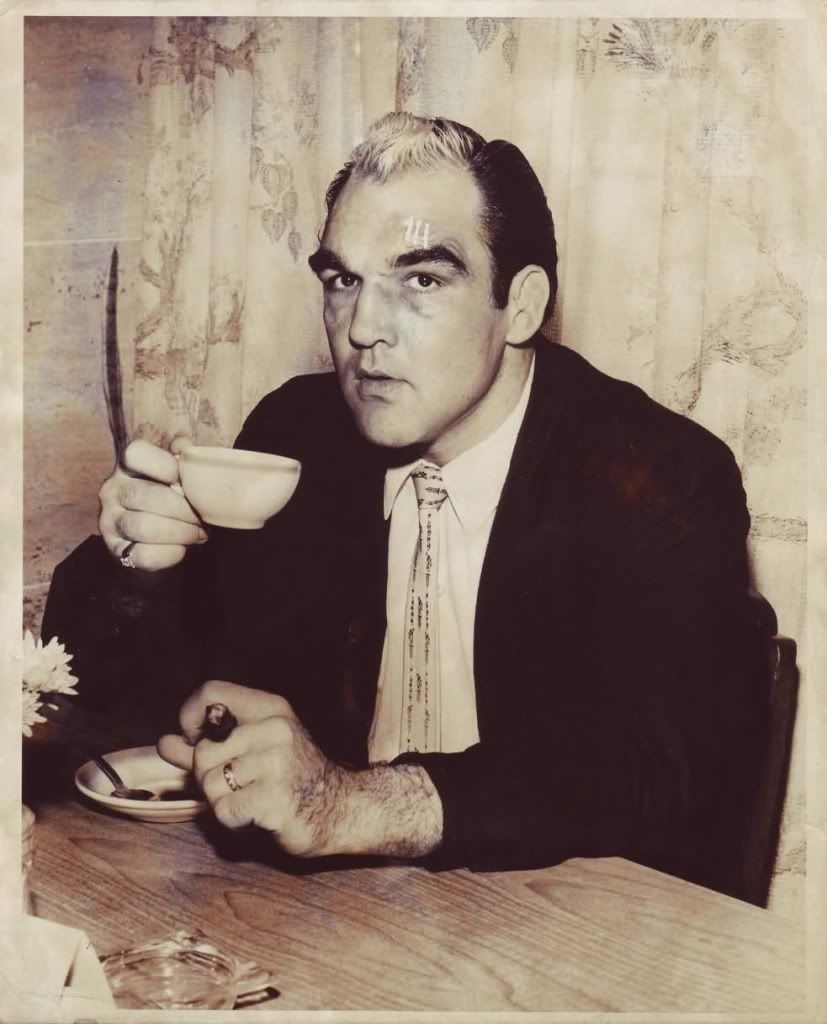

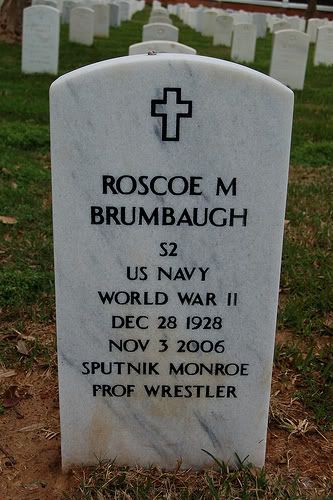

The other key figure to arrive in late 1958 would very quickly become simultaneously the most famous, infamous, loved, and hated wrestler in Memphis: the incomparable Sputnik Monroe.

A man who embraced a moniker that would be considered the worst thing to be called in America in the 1950's, Monroe kept the name Sputnik after being called such by an elderly white lady who saw him giving a ride to a black hitchhiker and making his acquaintance. She referred to him as "nothing more than a damned Sputnik."

At 235 pounds "of twisted steel and sex appeal," Monroe quickly became a headlining heel in Memphis. One of his first matches in the territory ended, as the Memphis paper put it, "in disqualification after stomping the referee, among other things."

Monroe's unique ability to incense a crowd clashed perfectly with the heroic image of Wicks, which Fuller saw as the potential lightning in a bottle formula he was looking for to take the Memphis wrestling scene to the next level.

Shortly after Monroe's death in 2006, Fuller's son Robert gave a point of view of Monroe's affinity with the crowd: "He was really pretty much just full of shit, but I learned an awful lot from him as a young guy. I got a lot of that ‘full of shit' from him. Sputnik would go to the ring, he'd start the match off as if he'd never worked the town before it. He'd make the jump for top rope and miss it before the match would even start, selling his back like crazy. Then he'd get up, madder than hell at the referee, saying the ropes weren't tight enough to make his jump over the top. He'd find 14 reasons why he busted his ass."

The buildup to their eventual feud had Wicks in tag battles against the Corsican Brothers for the Tag Team Championship while Monroe was booked in the classic wrestler-boxer program with former Light Heavyweight Champion Joey Maxim and then in an even more classic gimmick match of the time: against Brownie, a 400 pound wrestling bear.

The gimmick matches with Monroe worked in Fuller's favor and the attendance numbers were on the rise. All the while, the feud between Monroe and Wicks was beginning to take shape as well. Their first encounter would be April 6, 1959, a best of three falls, 90 minute time limit affair that Monroe won, setting up a rematch a week later. The second meeting went Monroe's way as well. In both cases, Ellis Auditorium was at full capacity.

It was during the spring of 1959, Fuller put into motion a tournament to crown an NWA Tennessee State Champion, which would be the backbone of Memphis wrestling shows through the months of May and June. Monroe and Wicks were again on an inevitable collision course.

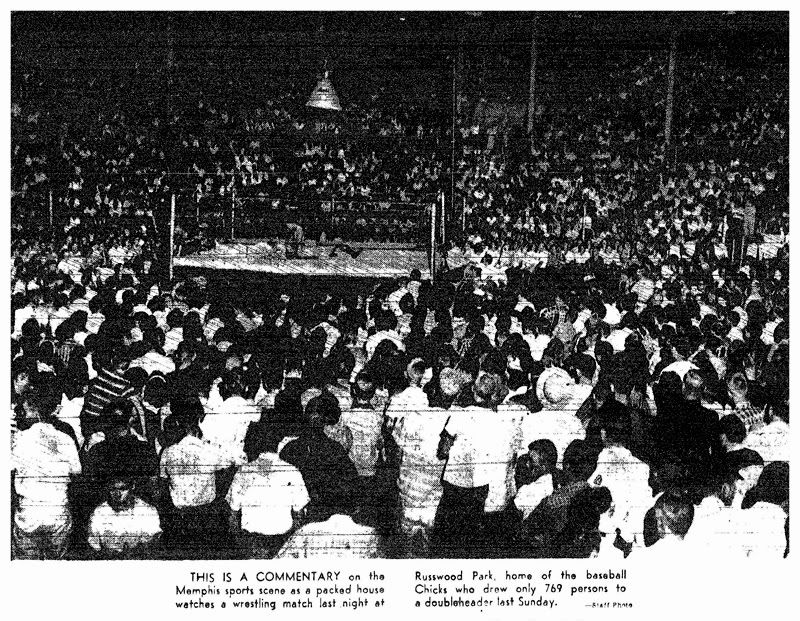

As the tournament progressed into June, Fuller's attendance figures were burgeoning beyond the confines of Ellis Auditorium, forcing the promoter to move the June 22 semi-final show to Crump stadium where 5,000 fans were on hand to see Monroe and Wicks win their respective bouts to set up the biggest wrestling match the city had ever seen.

…

Throughout Memphis, whose population had swelled to nearly 600,000 (nearly double where it had been in 1950), both Wicks and Monroe had also swelled to beyond cult status as two of the most recognizable figures in the city. Wicks, the upstanding hero was the ultimate babyface, revered throughout the cityscape.

Monroe, on the other hand continued to garner notoriety not only spurning the live crowd with his antics, but also outside of the ring as a hard drinker and "frequent cusser."

But there was something of a fascination with Monroe that could not be denied. Yes he was accurately portrayed as a stereotypical wrestling heel, but he was anything but a man of convention.

What became prevalent was that Monroe was a champion for the blacks in Memphis, stemming back to the initial incident that gave him his wrestling handle. Frequently, Monroe found company with blacks down on Beale Street in Memphis, and became an unlikely champion in the battle of racial desegregation.

Monroe's rebelliousness and inability to conform created an anti-hero persona around him that made him as much a simultaneous hero as he was a villain. And he never seemed to stray from controversy. One particular incident had him break the cane of television star Gene Barry (of the Bat Masterson television series), which instigated a brawl that made the front page of the next day's paper. (To put into perspective how big this was, the same paper carried a story about President Eisenhower's heart condition… which was a small piece at the bottom of the page.)

…

The finals of the Tennessee State Championship took place on June 29, 1959. Buddy Fuller's careful, methodical booking had created a heavy demand in Memphis to see the next chapter in the rivalry of Monroe and Wicks. This time, the stakes were at their highest.

In classic booking fashion, Wicks bested Monroe to become the inaugural NWA champion for the state of Tennessee. Monroe challenged Wicks unsuccessfully in their rematch a couple of weeks later, but on August 3, Monroe claimed the belt in a best of three falls match that drew 10,000 patrons at Russwood Park (a screw job finish that had Treacherous Phillips interfere on behalf of Monroe.)

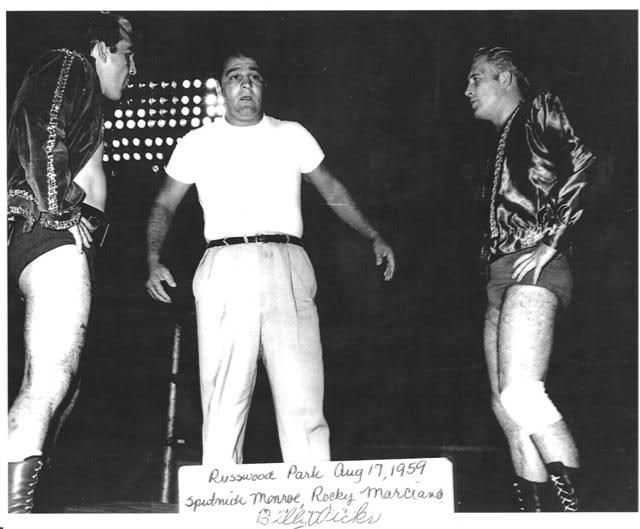

Wicks bested Phillips the next week in their brief quarrel and set up his rematch for the title against Monroe on August 17, 1959. Both Monroe and Wicks would get $500 for match, but the winner would also receive a 1959 Cadillac as a prize. Fuller created even more anticipation for the match by paying former undefeated boxing champion Rocky Marciano $5,000 to be the special guest referee.

With ticket sales soaring, Fuller once again moved the event to Russwood Park, where only three years before Elvis Presley had performed to a crowd of 14,000 fans. The reported number of tickets sold the night of the Monroe-Wicks championship bout reached 20,000. (Some sources have this actually recorded anywhere between 17,000 and 18,000.) Either way, Monroe and Wicks outsold the King and set an attendance record in Memphis that stood until the era of the Monday Night Wars between the WWF and WCW. The finish of the match had Marciano stopping the match, ruling it a "no decision" after the action got out of control. Monroe confronted Marciano about the finish and was promptly knocked down by a big right hand in the middle of the ring.

The show was historical for Memphis and was certainly influential in bringing the national wrestling spotlight to Tennessee. Monroe would get one more victory against Wicks in September before dropping the belt to "The Mighty Yankee" shortly after.

Fuller would cool the feud for the remainder of the year, but would put another clever spin on it when he would have Monroe and Wicks tag together against the Corsican Brothers in February of 1960 before having them battle each other again for the Tennessee Championship throughout the year.

…

The legacy of the Monroe-Wicks feud is the culmination of a perfect storm of elements that created instant recognition in the Memphis territory. With the combination of Gulas/Welch funding the operation and Buddy Fuller doing the leg work as promoter combined with the chemistry of Monroe and Wicks, wrestling was launched to another level of popularity in Memphis that would continue throughout the decades of the territory system in professional wrestling.

Billy Wicks would continue to wrestle in the territory before finally retiring in 1972 to become a patrol officer for the Memphis Sheriff department.

Sputnik Monroe would leave Memphis for Louisiana in 1960 but would make returns to the city over the years. He made his final wrestling appearance in 1998 at the age of 70. Upon returns to Memphis, Monroe would still find himself the object of continued fanfare. "I get kissed by people on Beale Street who didn't see me wrestle. They heard from their parents or grandparents what I had done and thanked me for doing it. That's pretty emotional, to have people walk up on the street and hug you and tell you ‘thank you' for something you did 40 years ago. Its hell to see the toughest son of a bitch in the world cry when that happens." (credit http://davehoekstra.tumblr.com/post/506685176/sputnik-monroes-memphis)

In July of 2005, nearly 45 years after their legendary, record breaking battle in Memphis, both Monroe and Wicks rekindled their feud as part of a special Memphis legends reunion. Despite being slow moving at 76, Monroe one last time gave the crowd his trademark strut. Wicks leaned into Monroe, telling him he would bust his glasses. Monroe laughed in return, replying "Oh, goddammit Wicks, I'll be blind. I can't see. I'll bleed to death!" (credit http://slam.canoe.ca/Slam/Wrestling/2006/11/03/2220366.html)

Sadly, Monroe passed away on November 3, 2006 due to complications from cancer and gangrene. The Rock ‘n Soul Museum in Memphis honored Monroe with a display of his entrance jacket and wrestling trunks. An icon forever.

As Wrestlemania is a time to honor and look back on the great wrestlers and matches of yesteryear, the cultural phenomena created in Memphis in 1959 was groundbreaking for the business on multiple levels from the savvy booking all the way down to incredible in-ring chemistry that could tell a story that would keep fans coming back for more. Sorry Rock and Cena, but you've got nothing on Monroe and Wicks.

No comments:

Post a Comment